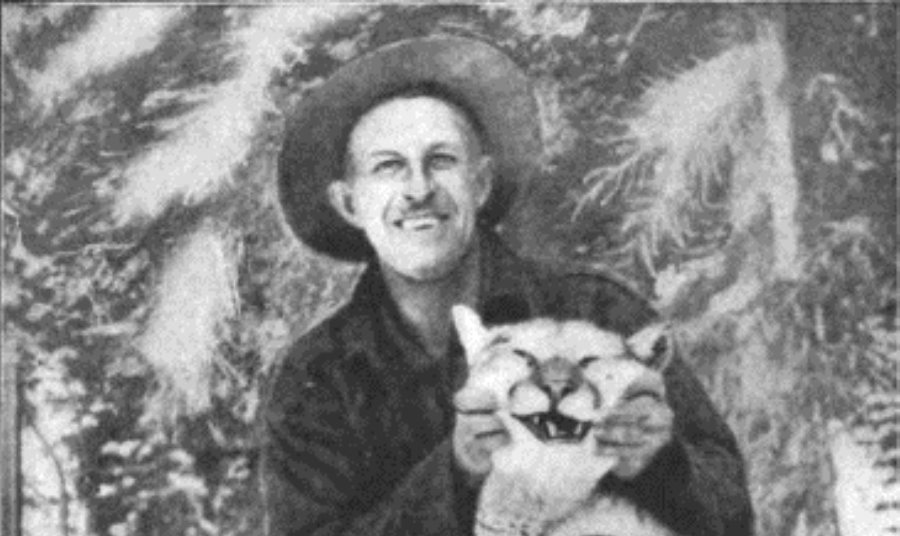

Back when men were truly men, before the American people were softened by the comforts of Doordash and online shopping, there was a lot of money to be made in the yet untamed North American wilderness. Adventurers like C. J. Lincke would embark on months-long expeditions into the virgin forests in search of fun and profit.

A Winter of Work—and Fur

In the winter of 1920, Lincke and his associate Charles Johnston had gone into the Canadian Rockies to exploit the region’s mineral wealth through copper mining. Their mining cabin, an isolated structure 80 thousand feet above sea level, was well supplied since the two expected to leave only during the spring thaw, when the going would be easier. To break up the monotony of their work, they would hunt and lay traps in the woods near their camp, occasionally bagging fur-bearing animals like martens which would sell for no small amount of cash back in civilization. A single black marten would be worth $65 or $950 in today’s money.

The Disappearing Game

One day, the two discovered many of their traps had been broken into by some… creature. From trap to trap, the snow had been disturbed and the traps had been set off, but the lynxes and martens that were supposed to be there were conspicuously missing as well, along with their valuable furs. At first, Lincke and Johnston believed they had fallen victim to a wolverine. After all, the ravenous creatures were also known to scavenge from time to time. The pair figured it wasn’t such a big loss, and they could just reset the traps for the next day.

A Sudden Avalanche and a Sinister Shadow

Unfortunately, mother nature had different plans. That night, the earth shook, and a cascade of snow and earth from the mountaintops rushed into the valley below, turning it into a white sea with only the treetops of the tall evergreens reaching out from the vast white desert.

This was no small emergency, and the two men decided to pick their way through and journey to another log cabin deep in the woods, following a wide gulch to the area where they knew the snow was shallower. As they trekked through the dense forest, Lincke picked up a set of tracks running parallel with their own. Mountain lion tracks.

Stalked Through the Snow

Now, your average yellow-bellied city slicker would most likely turn tail and head back to the snow-logged cabin and just wait in misery for the spring thaw rather than risk going toe-to-toe with a mountain lion, but Lincke and Johnston were made of sterner stuff. Armed only with an axe, they continued the trek. It would be another four miles to reach the other cabin, where Lincke had left his rifle.

As night fell, Lincke produced a device called a “bug light,” essentially a candle in a tomato can with a bucket handle. There were holes cut into it to let the light shine out, and it made a good makeshift lantern.

After a mile of hiking in the darkness, Lincke noticed what he called “a faint echo of (their) footsteps” coming from their rear. As he shone the bug light to the path behind them, he caught sight of what he described as two orbs of “green fire” staring at them from the shadows.

Preparing for a Fight

Running was out of the question. In snow that deep, with walking already as hard as it was, going any faster was a near impossibility. If the lion pounced, the two had agreed that whoever was attacked first would curl up into a ball and use his rucksack to bear the brunt of the lion’s assault while the second man would grab an axe and counterattack.

Thankfully the lion retreated into the shadows, most likely because it knew its potential prey was looking directly at it. Lincke and Johnston moved on, picking up the pace as much as the thick snow allowed them to. Lincke described the rest of the trip as a lethal game of hide and seek, with the soft crunch of the cat’s paws following them all the way.

Occasionally, it would appear behind them or on their flanks, considering an attack only to be driven off by the slowly dimming light of their bug light.

Cabin Defense

By nothing short of a miracle, they reached the safety of their cabin. As luck would have it, this building was just as snowed in as their last cabin, and the two had to shovel snow in the dark to even find the door. After they had made their way inside and settled down a bit, Johnston decided to make some tea using melted snow from outside.

As he opened the door, he found a pair of hungry green eyes staring down at him from the edge of the snow pile in the doorway. Johnston slammed the door shut on the creature just before it pounced. Both men heard the loud thud against the door’s solid wooden panel.

Lincke grabbed his rifle, a faithful lever-action, and trained it at the door. It was here they would make their stand. He signaled for Johnston to open the door, and as he did so, nothing came in but the cold winter air.

Relieved, Johnston closed the door again. Both men trusted they would be well defended by their wooden cabin. Snow had covered all the windows and was level with the roof, and the only viable entryway was guarded by Lincke and his rifle.

Tracking the Beast

The rest of the night was uneventful. By morning, when the pair came out to stretch their legs, they noticed the big cat had encircled the cabin multiple times trying to find a way in, even walking over the roof in frustration.

Something needed to be done.

After stuffing their packs with three days’ worth of provisions and blankets and arming themselves with the axe and the rifle, the pair of adventurers followed the beast’s tracks back into the woods.

As an expert tracker, Lincke saw the tracks more than a set of footprints leading to an animal. Rather, he could read them as a story in the snow. From its tracks, he traced the mountain lion’s path to beyond a 20-foot deadfall, from which it had leapt down. A scattering of feathers and two sets of prints pointed to a scuffle between the mountain lion and a grouse, which had escaped. Further down the trail, a different set of tracks crossed those of the mountain lion – a hare chased by a lynx – but after those tracks met, only the hare’s tracks bounded off into the wilderness, while the lynx’s paw prints disappeared completely.

The Final Chase

After two hours of tracking, they spotted a flash of tawny behind a large tree. Before Lincke could take proper aim, the big cat was gone. After circling around the tree, they could find no sign of the animal, but its tracks gave them a good idea of where it was.

The two men decided to split up and spread out, hoping to flush the mountain lion out of the woods into the open gulch. Johnston, only armed with an axe, must have been scared out of his mind, but luckily the mountain lion knew it was being stalked, and its sense of self-preservation made it retreat.

As the two men passed through the forest and into an open glade, they saw the mountain lion several hundred yards out, much too far for an accurate shot with a lever-action. It was trying to run in the snow, which was belly deep for the cat in some places. Occasionally it would turn and hiss at the two men before continuing its retreat.

The depth of the snow made the going rough for everyone. It was more of a slog than a chase, and the mountain lion would sometimes disappear into the deep snow as if it were water, only to reappear again somewhere else like a tan-colored whale breaking the surface.

The Shot and the Rug

Somewhere during the chase, the lion decided to make a detour and headed back towards the cabin. Eager to not have the animal break into their camp, the men picked up the pace and found the creature in a thick growth of hemlock leaping from a deadfall to a large log, pausing just long enough for Lincke to take a shot.

The crack of the lever-action rifle rang through the forest, but only grazed the cat’s throat. The lion leapt up into the trees, taking cover amidst the thick evergreen needles. The two men circled the trees, drawing nearer to try and corner the lion.

A flash of tan fur 25 feet up gave away the cat’s position. Just as it was about to pounce on Johnston, Lincke fired and struck the lion under the head. It hit the snowy forest floor like a ton of bricks. When their heart rates slowed down and the excitement wore off, the two men realized they were no more than a hundred yards from the cabin. They doffed their hats for the lion, giving the great cat the respect it deserved and thanking it for allowing them to kill it so close to their cabin so they could skin it in comfort.

When they opened it up, they discovered the lost furs from their traps, as well as the remains of a lynx. Along the cougar’s front legs and belly, there were several lacerations made from lynx claws. The animal had apparently put up quite a fight before it went down.

The lion measured eight feet six inches from nose to tail, and Lincke turned the great cat into a bedroom rug.

The Modern Hunter's Advantage

Nowadays, the number of adventurers and hunters who would take risks like Lincke and Johnston is dwindling, but for those who would, they wouldn’t have to fear being stalked in the dark thanks to technological innovations like the Wraith Thermal, Sightmark’s powerful new thermal riflescope.

Capable of defeating all manner of camouflage, the Wraith Thermal is accurate and deadly efficient, just like the great predators that stalk the shadows of what wilderness remains.

Urgent: Colorado's Initiative 127 seeks to ban all manner of big cat hunting, and could deal a grave blow to wildlife management in the region. Read about it here.